Providers Well-Being

Online Tools

Online Self-Help

Education About Depression

Depression: Symptoms and Warning Signs Helping Someone with Depression The Vicious Cycle of Depression Coping with Negative Thinking in DepressionEducation About Suicidality

Dealing with Suicidal Thoughts and Feelings How to Help Someone Who is SuicidalExercise & Staying Motivated

Tips for Staying MotivatedMindfulness & Self-Compassion

What is Mindfulness? (video) The Science of Self-Compassion (video) Simple Ways to Practice Mindfulness Daily Self-Compassion Meditations and ExercisesNutrition

Nutrition FactsTraumatic Stress:

What is it? What do I do about it?

Coping with Traumatic Stress

Screen Your Well-Being

Please note, the results of these assessments are not diagnostic, rather a place to start the conversation about your personal health and well-being. You can also track your well-being over time, and access helpful resources based on your results.

Anxiety

Anxiety Screening Quiz Anxiety Quiz Anxiety Test Stress and Anxiety Quiz Anxiety TestBurnout

Burnout Self-Test Burnout Test - Service Fields Burnout Test - Service FieldsDepression

3 Minute Depression Test Depression Test Depression Test Depression ScreeningEmotional Intelligence

Emotional Intelligence Test Emotional Intelligence QuizHappiness

Authentic Happiness How Happy are You? Happiness TestMindfulness

Mindfulness Quiz 5 Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire How Mindful are You?Physical Fitness

How fit are you?Self-Compassion

Self Compassion Guided Practices and Exercises Test How Self-Compassionate You AreSleepiness

For Sleep SupportStress

Stress Screener How Stressed Are You?Substance Use

Rethinking Drinking Alcohol and Drug Assessment NIDA Drug Screening ToolWell-Being Help Center

COVID-19 Mental Health Support Line

The BSOM Department of Psychiatry has set up a COVID-19 Mental Health Support line for all our providers. BSOM Psychiatry faculty will be staffing the phone line 937-775-8140 Monday - Friday from 12 p.m. - 8 p.m. The attending psychiatrists on the line will be offering educational resources, coping strategies, building resilience, and other screening and linkages as appropriate for providers who may need mental health support during this time. All calls will be handled confidentially.

Process to Access

- Dayton Behavioral Care will partner with Kettering Health Network to provide free psychosocial support for any member of the medical staff, administration or APPs needing to talk with a mental health professional during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- To access this care:

- Please send email to:

- Please provide a name, good contact number, preferred way of communication (phone or email), and a good time to call.

- Subject line of the email: COVID-19 Health Care Worker

- All communications will be handled confidentially.

Well-Being Care Service

wellbeingcare.org: A free, anonymous service is being made available to help healthcare workers throughout Ohio screen for mental and emotional health issues and, if needed, connect with licensed mental health professionals and resources.

Free Crisis Hotlines & Chat Lines

- IMALIVE: A confidential and secure chat line supporting people in crisis or considering suicide.

- SAMHSA's National Helpline: 1-800-662-4357(HELP) - Available 24/7 geared toward substance abuse related circumstances that can attribute to depression, burnout, and suicide.

- Crisis Text Line: Available 24/7 by texting TALK to 74174.

- The Sara Charles MD Physician Litigation Stress Resource Center

- Physician Litigation Stress Resource Blog

- Lifeline Crisis Chat: Available 24/7 providing online emotional support, crisis intervention, and suicide prevention services.

- Assistance Program by IMPACT Solutions: 1-800-227-6007 - A program provided by Kettering Health that is available to you, your household members and dependents offering access to confidential, live, in-the-moment support, 24/7/365.

- Emotional PPE: They connect healthcare workers in need with licensed mental health professionals who can help. No cost. No insurance. The Emotional PPE Project is a directory that provides contact information of volunteer mental health practitioners to healthcare workers whose mental health has been impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. It is fully staffed by volunteers.

- For the Frontlines: This 24/7 help line provides free crisis counseling for frontline workers. They can text FRONTLINE to 741741 in the United States (support is also available for residents of Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom).

- Project Parachute is a project aimed to provide pro-bono therapy for frontline healthcare professionals.

Helping Others

Physician suicide rates are high. Nearly 1 in 4 physicians know a physician who has died by suicide. It's estimated that a million Americans lose their

physician to suicide every year. Why? Because there's stigma surrounding mental health and seeking help. The majority of medical systems lack support for

physicians dealing with stress and traumatic events. Administrative and regulatory burdens take away from the joy of practicing medicine.

If you know a colleague or loved one that is struggling, opening your heart and reaching out to them can be a critical first step in

helping them get the support they need.

Learn more

Mental Health Counseling

Personal or psychological counseling offers you the opportunity to talk about social, emotional, or behavioral problems that are either causing you distress or interfering with your functioning. These encounters occur in a safe forum, knowing that what is shared will be kept private and confidential. mental health counselors are trained professionals who can respond to your concerns in an objective and non-judgmental manner and offer guidance to individuals, couples, families and groups who are dealing with issues that affect their mental health and well-being.

Mental health counseling improves and even saves lives. Seeking counseling is a sign of courage and strength because it's an important step in taking charge of mental health and creating the life that you deserve, a life worth living

There are many reasons for pursuing personal or psychological counseling:

Most Common Needs:

- Family or relationship conflict

- Issues of grief and loss

- Difficulty managing stress

- Coping with traumatic events

- Domestic violence or sexual assault

- Depression or lack of motivation

- Anxiety or acute panic attacks

- Problems with alcohol or other drugs

- Problems with anger compulsive behaviors

Benefits of Counseling:

- Decreased problems with daily living

- Increased sense of joy and contentment

- Repaired and enhanced relationships

- Improved functioning at work

- Increased activity- reduced social isolation

- Increased quality of life and overall life satisfaction

Choosing a qualified mental health counselor can be challenging. To help support you in your counseling needs, the wellbeing team is compiling a list of qualified and recommended mental health counselors who practice outside of the network, preserving your confidentiality and anonymity.

Elaine M. Pritchett, MS, LPCC-S

Elaine is a licensed clinical counselor working with individuals, couples and families in the Dayton area over the last 14 years. Elaine is a highly skilled, compassionate, solution-oriented professional dedicated to providing meaningful services to those experiencing a wide variety of mental health concerns ranging in severity and duration. Elaine is an effective motivator, communicator and advocate with inherent ability to interact with all types of personalities, defuse stressful situations and proactively assist individuals in resolving challenges. Elaine's clinical interests and concentrations include, PTSD and Grief recovery, Anxiety, Depression, Life Stress management. She has co-authored an article" Perceptions of Clients and Counseling Professionals Regarding Spirituality in Counseling" in Counseling and Values Journal.

Contact Info

Elaine Pritchett

1948 E. Whipp Rd. Suite A-1

Dayton, Ohio 45440

Office: 937-477-4421

- Preferred

- Accepts major insurance plans except Aetna & Humana.

- Available for telehealth visits.

- Resident visits at no cost to residents.

Beth Collins, MS, LPCC-S

Beth is a Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor. A member of the American Counseling Association, Ohio Counseling Association, Miami Valley Counseling Association, and the American Association of Christian Counselors. Beth has training in wellness, working with clients who have been through traumatic situations, those with anxiety or depression, parents of children with ADHD and behavioral issues, anger management and problem solving. Additional training includes Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Level 2 Training, Gottman Method Couples Therapy, Professional Life Coaching.

Contact Info

Beth Collins

Joy in the Balance, LLC

1930 N Lakeman Ave Ste 103,

Bellbrook OH 45305

Office: 937-602-2820

www.Joyinthebalance.com

- Accepts most insurance plans, see website for details.

- Available for telehealth visits.

- Resident visits at no cost to residents.

Stephen Fortson, EdD, PCC-S

Stephen has been involved with providing professional counseling services since 1994. He completed his graduate training at Wright State University and the University of Cincinnati, receiving a doctorate in counseling in 1994. He retired from Wright State University in 2020, after 27 years of service. He chaired the Department of Human Services for 20 years, guiding the counseling, rehabilitation counseling, and Sign Language programs. He has been in private practice in Centerville since 2016, working initially with Melissa Strombeck and now in his own independent private practice. He specializes in treating anxiety, depression, grief and loss, life transitions, burnout, work related issues and marriage counseling. He also has been offering self-care and wellness training for the residents of KHN since 2016.

Contact Info

Stephen Fortson

257 Regency Ridge

Dayton, Ohio 45459

Office: 937-437-9015

- Available for telehealth visits.

- Resident visits at no cost to residents.

Lewis Nevins, PCC

Lewis is a Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor at Professional Counseling and Consulting in Kettering, Ohio. He has been practicing since 2009. He emphasizes establishing rapport and trust with his clients by developing a strong therapeutic relationship with them and values a client's ability to make responsible choices. He has worked with various healthcare providers and understands the challenges and demands of this work. Lewis specializes in treating trauma, anxiety, depression, and relational problems. He has trained in CPT, DBT, IFS, CBT, and Mindfulness-based practices.

Contact Info

Lewis Nevins

1948 E Whipp Rd Suite A1

Kettering OH 45440

Office: 937-434-6217 - Ext 3

- Available for telehealth visits

- Resident visits at no cost

Well-Being Resources

Wellbeing Apps:

Download from your APP Store

Dr. Greger's Daily Dozen

Dr. Greger's Daily Dozen

Provider Resilience (Free)

Provider Resilience (Free)

Breathe2Relax (Free)

Breathe2Relax (Free)

Virtual Hope Box (Free)

Virtual Hope Box (Free)

MyLife (Free)

MyLife (Free)

Mindfulness Coach (free)

Mindfulness Coach (free)

CBT-i Coach - (Free)

CBT-i Coach - (Free)

(specifically helps to address insomnia or other sleep-related issues)

Fitness Apps:

Download from your APP Store

Nike training club

Nike training club

Carrot fit

Carrot fit

Sling TV

Sling TV

Down Dog apps

Down Dog apps

Planet Fitness on FB and app

Planet Fitness on FB and app

19 minute yoga

19 minute yoga

Fitness Blender - No App, Website only

Fitness Blender - No App, Website only

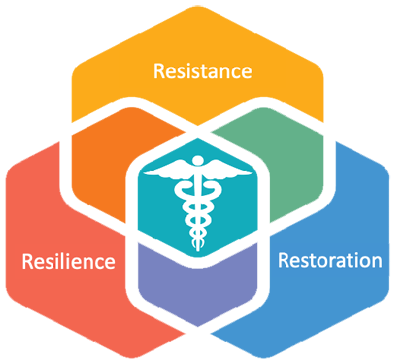

Resiliency Tools:

The resilience tools are evidence-based, interactive, and specifically designed for busy healthcare workers. Interventions last between 3-15 days. Participants will receive prompts for the tools via email or text message.

The resilience tools are evidence-based, interactive, and specifically designed for busy healthcare workers. Interventions last between 3-15 days. Participants will receive prompts for the tools via email or text message.

Duke Resiliency Tools

Workout videos for every fitness level. Absolutely free!

Workout videos for every fitness level. Absolutely free!

3 months free (open to anyone) to address COVID-19 induced anxiety

3 months free (open to anyone) to address COVID-19 induced anxiety

WFMZ-TV 69 News Article with link to Free App

If you are a healthcare worker and are not currently subscribed to Ten Percent Happier, we would like to support you by offering free access to the app - please email care@tenpercent.com for instructions. https://www.tenpercent.com/coronavirussanityguide

If you are a healthcare worker and are not currently subscribed to Ten Percent Happier, we would like to support you by offering free access to the app - please email care@tenpercent.com for instructions. https://www.tenpercent.com/coronavirussanityguide

This free app has been made available for three months to support physicians, APP's and anyone with an NPI number to login. https://www.headspace.com/covid-19

This free app has been made available for three months to support physicians, APP's and anyone with an NPI number to login. https://www.headspace.com/covid-19

Mobile Apps: COVID Coach

The COVID Coach app was created to support self-care and overall mental health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/appvid/mobile/COVID_coach_app.asp

Events

Articles

| Nov 30, 2023 |

Rx for Resilience: Five Prescriptions for Physician Burnout -Rachel Reiff Ellis |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Physician burnout persists even as the height of the COVID-19 crisis fades farther into the rearview mirror. The causes for the sadness, stress, and frustration among doctors vary, but the effects are universal and often debilitating: exhaustion, emotional detachment, lethargy, feeling useless, and lacking purpose. When surveyed, physicians pointed to many systemic solutions for burnout in Medscape's Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023, such as a need for greater compensation, more manageable workloads and schedules, and more support staff. But for many doctors, these fixes may be years if not decades away. Equally important are strategies for relieving burnout symptoms now, especially as we head into a busy holiday season. Because not every stress-relief practice works for everyone, it's crucial to try various methods until you find something that makes a difference for you, says Christine Gibson, MD, a family physician and trauma therapist in Calgary, Canada, and author of The Modern Trauma Toolkit. Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023, such as a need for greater compensation, more manageable workloads and schedules, and more support staff. But for many doctors, these fixes may be years if not decades away. Equally important are strategies for relieving burnout symptoms now, especially as we head into a busy holiday season. Because not every stress-relief practice works for everyone, it's crucial to try various methods until you find something that makes a difference for you, says Christine Gibson, MD, a family physician and trauma therapist in Calgary, Canada, and author of The Modern Trauma Toolkit. Symptoms Speak Louder Than WordsIt seems obvious, but if you aren't aware that what you're feeling is burnout, you probably aren't going to find effective steps to relieve it. Jessi Gold, MD, assistant professor and director of wellness, engagement, and outreach in the department of psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, is a psychiatrist who treats healthcare professionals, including frontline workers during the height of the pandemic. But even as a burnout expert, she admits that she misses the signs in herself. "I was fighting constant fatigue, falling asleep the minute I got home from work every day, but I thought a B12 shot would solve all my problems. I didn't realize I was having symptoms of burnout until my own therapist told me," says Gold. "As doctors, we spend so much time focusing on other people that we don't necessarily notice very much in ourselves—usually once it starts to impact our job." Practices like meditation and mindfulness can help you delve into your feelings and emotions and notice how you're doing. But you may also need to ask spouses, partners, and friends and family — or better yet, a mental health professional — if they notice that you seem burnt out. Practice 'in the Moment' ReliefSometimes, walking away at the moment of stress helps like when stepping away from a heated argument. "Step out of a frustrating staff meeting to go to the bathroom and splash your face," says Eran Magan, PhD, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania and founder and CEO of the suicide prevention system EarlyAlert.me. "Tell a patient you need to check something in the next room, so you have time to take a breath." Magan recommends finding techniques that help lower acute stress while it's actually happening. First, find a way to escape or excuse yourself from the event, and when possible, stop situations that are actively upsetting or triggering in their tracks. Next, recharge by doing something that helps you feel better, like looking at a cute video of your child or grandchild or closing your eyes and taking a deep breath. You can also try to "catch" good feelings from someone else, says Magan. Ask someone about a trip, vacation, holiday, or pleasant event. "Ask a colleague about something that makes [them] happy," he says. "Happiness can be infectious too." Burnout Is Also in the Body"Body psychotherapy" or somatic therapy is a treatment that focuses on how emotions appear within your body. Gibson says it's a valuable tool for addressing trauma and a mainstay in many a medical career; it's useful to help physicians learn to "befriend" their nervous system. Somatic therapy exercises involve things like body scanning, scanning for physical sensations; conscious breathing, connecting to each inhale and exhale; grounding your weight by releasing tension through your feet, doing a total body stretch; or releasing shoulder and neck tension by consciously relaxing each of these muscle groups. "We spend our whole day in sympathetic tone; our amygdala's are firing, telling us that we're in danger," says Gibson. "We actually have to practice getting into and spending time in our parasympathetic nervous system to restore the balance in our autonomic nervous system." Somatic therapy includes a wide array of exercises that help reconnect you to your body through calming or activation. The movements release tension, ground you, and restore balance. Bite-Sized Tools for Well-BeingBecause of the prevalence of physician burnout, there's been a groundswell of researchers and organizations who have turned their focus toward improving the well-being in the healthcare workforce. One such effort comes from the Duke Center for the Advancement of Well-being Science, which "camouflages" well-being tools as continuing education credits to make them accessible for busy, stressed, and overworked physicians. "They're called bite-sized tools for well-being, and they have actual evidence behind them," says Gold. For example, she says, one tools is a text program called Three Good Things that encourages physicians to send a text listing three positive things that happened during the day. The exercise lasts 15 days, and texters have access to others' answers as well. After 3 months, participants' baseline depression, gratitude, and life satisfaction had all "significantly improved." "It feels almost ridiculous that that could work, but it does," says Gold. "I've had patients push back and say, 'Well, isn't that toxic positivity?' But really what it is is dialectics. It's not saying there's only positive; it's just making you realize there is more than just the negative." These and other short interventions focus on concepts such as joy, humor, awe, engagement, and self-kindness to build resilience and help physicians recover from burnout symptoms. Cognitive Restructuring Could WorkCognitive restructuring is a therapeutic process of learning new ways of interpreting and responding to people and situations. It helps you change the "filter" through which you interact with your environment. Gibson says it's a tool to use with care after other modes of therapy that help you understand your patterns and how they developed because of how you view and understand the world.

"The message of [cognitive-behavioral therapy] or cognitive restructuring is there's something wrong with the way you're thinking, and we need to change it or fix it, but in a traumatic system [like healthcare], you're thinking has been an adaptive process related to the harm in the environment you're in," says Gibson. "So, if you [jump straight to cognitive restructuring before other types of therapy], then we just gaslight ourselves into believing that there's something wrong with us, that we haven't adapted sufficiently to an environment that's actually harmful." Strive for a Few Systemic ChangesSystemic changes can be small ones within your own sphere. For example, Magan says, work toward making little tweaks to the flow of your day that will increase calm and reduce frustration. "Make a 'bug list,' little, regular demands that drain your energy, and discuss them with your colleagues and supervisors to see if they can be improved," he says. Examples include everyday frustrations like having unsolicited visitors popping into your office, scheduling complex patients too late in the day, or having a computer freeze whenever you access patient charts. Though not always financially feasible, affecting real change and finding relief from all these insidious bugs can improve your mental health and burnout symptoms. "Physicians tend to work extremely hard in order to keep holding together a system that is often not inherently sustainable, like the fascia of a body under tremendous strain," says Magan. "Sometimes the brave thing to do is to refuse to continue being the lynchpin and let things break, so the system will have to start improving itself, rather than demanding more and more of the people in it." https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/five-resilience-rx-physician-burnout-2023a1000tr1?ecd=wnl_dne1_231130_MSCPEDIT_etid6109442&uac=69465HR&impID=6109442 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 22, 2023 |

Preventing Physician Suicide |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eight hundred thousand deaths worldwide were attributed to suicide in 2016.1 In the same year in the United States, age-standardized suicide rates were 21.1 and 6.4 deaths per 100 000 persons, for men and women, respectively.1,2 Historically, data collected up to the 1980s showed age-standardized suicide rates were significantly higher for physicians than the general population, including much higher rates for female physicians and moderately higher rates for male physicians.3 However, more recent data suggest that while female physicians continue to have higher suicides rates than the general female population (standardized mortality ratio of 1.46), male physicians actually have a lower suicide rate than the general male population (standardized mortality ratio of 0.67).4 Further research on this digression based on sex is crucial. Physicians are not at greater risk for suicide than the general population because they are “weaker” or less resilient; rather, the opposite is true. Despite their high levels of personal resilience, physicians are often placed in situations of recurrent stress. Recurrent stress can lead to physiological and physical exhaustion, otherwise known as burnout.5 Burnout now affects almost half of US physicians.6,7 Physician burnout is often characterized by depersonalization, including cynical or negative attitudes toward patients, a feeling of decreased personal achievement, and a lack of empathy for patients.8 Physician burnout and distress have been associated with higher rates of alcohol use disorder and depression, increased risk for suicide, lower quality of life, reduced cognitive functioning, and poor quality of patient care.9 While burnout and suicide are very much organizational-level problems and not individual ones, this toolkit addresses both individual actions (obtaining and offering support) as well as organizational ones (promoting an environment of wellness). Even though physicians agree they have an ethical obligation to intervene when they believe a colleague is impaired, many fail to report it appropriately.10 Taking proactive steps to identify and address physician distress can help to ensure the well-being of physicians, reduce the risk of suicide, and support patient care by protecting the health of the physician workforce.11 Although the information in this toolkit may be applicable to other clinical team members, the focus is on physicians' vulnerability and treatment needs. Furthermore, physicians-in-training, a vulnerable population with potentially higher risks of depression and suicide, are not specifically addressed in this toolkit; there are separate toolkits discussing medical student and resident/fellow burnout and well-being. Four STEPS to Identify and Support At-Risk Physicians

STEP 1 Identify Suicide Risk Factors and Warning Signs Suicidal behavior is a complex problem with no single cause or absolute predictors. Risk factors for physician suicide include13- 18:

Many physicians closely tie their identity to their professional image, making these physicians more vulnerable to distress when problems arise at work.19 It is important for all physicians to be aware of the warning signs of suicide, which can include19- 21:

It is vital to take action if you suspect a colleague is demonstrating warning signs for suicide. While not every suicide may be preventable, people with suicidal feelings can be helped. Speaking directly with your colleague is a good first step. You can say, “I'm concerned about you. Have you had any thoughts of harming yourself?” You do not need to be an expert to offer to help. Often, a simple recommendation to talk with a mental health professional can be an important first step. Facilitate confidential referrals to mental health care professionals by keeping an updated list of local and national resources that physicians can access discreetly (see further guidance in STEP 4). Physicians may be hesitant to talk to a colleague or supervisor because of the stigma or privacy concerns and may be more willing to access help from an outside source. STEP 2 Promote Care-Seeking Behaviors Although physicians recognize the value of obtaining treatment, they often are the most reluctant to access medical care and frequently receive poorer care than other patients (eg, fewer laboratory tests, less rigorous medical evaluations).23,24 Thus, it is essential for physicians to recognize the importance of self-care, model wellness behaviors, and encourage others to do the same. As a practicing physician, start by taking steps to maintain your health, including:

If these self-care tips are not enough, it is time to seek additional help. Physicians should refer themselves or colleagues to internal or external programs that, in most cases, can provide confidential services for voluntary referrals (see STEPS 3 and 4). As an organizational leader, foster a positive culture within your organization. Communicate widely and often with your team about the need to intervene if they suspect a colleague needs help. You can try some of these strategies:

STEP 3 Train a Physician Advocate Creating a supportive atmosphere in the workplace can be instrumental in addressing physician distress. You may consider having a person within your organization serve as a physician advocate. Enlist an individual, such as a human resource professional or a hospital wellness committee member, whom physicians would feel comfortable approaching. This individual must be trustworthy, discreet, and knowledgeable. Training the physician advocate is critical and should focus on explaining internal and external policies and implications regarding privacy, confidentiality, and care-seeking. The physician advocate should be prepared to answer physicians' questions about the potential impact that receiving mental health care may have on job security, medical licenses, medical liability insurance, and disability coverage. The physician advocate is responsible for distributing guidance on physician distress and suicide—and where to find support. Once a physician advocate is selected and trained, widely communicate this person's role and what type of support services are available. Forms of support include:

STEP 4 Make It Easy to Get Help Your organization should keep updated referral lists for confidential resources inside and outside your organization and make them readily available to all team members, including physicians. Almost every state in the country has a physician health program (PHP). Although programs vary, physician health programs provide or facilitate in-depth evaluations, appropriate treatment referrals, and, if necessary, monitoring for residents, physicians, and sometimes medical students. Because physician health programs are not affiliated with clinical practices or hospitals, they allow physicians to access private and confidential care. The Federation of State Physician Health Programs maintains a list of state physician health programs with a description of the services each program provides. Display these resources in a highly visible location that does not require a password and assures users that there is no tracing of page visits or downloads. Identify policy barriers to care-seeking in your organization and take steps to minimize them. Work with organizational leadership to examine and modify (if necessary) your internal policies to encourage care-seeking by physicians. In this review of organization policies, ask yourself:

If concerns about confidentiality prevent physicians with distress from seeking care, their condition may worsen. Policies allowing confidential access to treatment are more likely to encourage physicians to seek the care they need. Organizational leadership should consider this factor when developing confidentiality policies, as the risks of untreated physician distress often outweigh the potential benefits of mental health disclosures. For full article, visit https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702599 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jan 11, 2023 |

Physician Well-being 2.0: Where Are We and Where Are We Going? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AbstractAlthough awareness of the importance of physician well-being has increased in recent years, the research that defined this issue, identified the contributing factors, and provided evidence on effective individual and system-level solutions has been maturing for several decades. During this interval, the field has evolved through several phases, each influenced not only by an expanding research base but also by changes in the demographic characteristics of the physician workforce and the evolution of the health care delivery system. This perspective summarizes the historical phase of this journey (the “era of distress”), the current state (Well-being 1.0), and the early contours of the next phase based on recent research and the experience of vanguard institutions (Well-being 2.0). The key characteristics and mindset of each phase are summarized to provide context for the current state, to illustrate how the field has evolved, and to help organizations and leaders advance from Well-being 1.0 to Well-being 2.0 thinking. Now that many of the lessons of the Well-being 1.0 phase have been internalized, the profession, organizations, leaders, and individual physicians should act to accelerate the transition to Well-being 2.0. Abbreviations and Acronyms: EHR (electronic health record) Awareness of occupational distress among physicians and efforts to cultivate physician well-being have crescendoed in recent years. This awareness was amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which emphasized the foundational importance that well-being plays in physicians’ ability to serve patients and for health care organizations to achieve their mission. Although general awareness of the importance of physician well-being has increased during the past several years, the research that defined this challenge, identified the contributing factors, and provided evidence on effective individual and system-level responses has been maturing for several decades. The maturation of this field has evolved through several phases, each influenced not only by an expanding research base but also by changes in the demographic characteristics of the physician workforce and the evolution of the health care delivery system. This perspective summarizes the historical phase of this journey, current state, and insights regarding where we need to go next. The summary of each phase is intended to be descriptive rather than a critique and to illustrate how the field of physician well-being has evolved and matured. The Past: The Era of DistressThe historical era, or what I will coin the “era of distress,” was characterized by a lack of awareness, or even deliberate neglect, of physician distress. This phase largely described the field before 2005. Although early data on physician burnout and evidence of its potential repercussions on quality of care had begun to be chronicled, the issue of occupational distress was not a meaningful part of the conversation among the profession or society.Evidence from other fields that occupational burnout was a system issue originating from problems in the work environment, rather than a weakness in the worker, was not widely adopted by the field of medicine. Physicians were selected and winnowed through an arduous training process and were, in many ways, expected to be superhuman. Medical school and residency training were characterized by a “rites of passage” mindset that subjected physicians to unlimited work hours, often involving many consecutive days on duty with little sleep, rest, or breaks. The evolving science on sleep and human performance was not applied to physicians, who were expected to perform with equal excellence throughout the arc of extended-duty shifts independent of whether they had slept. Physicians worked regardless of whether they were ill, and there were few if any backup systems to provide coverage. If physicians were unable to report for work, their colleagues “picked up the slack.” For individual physicians, a desire not to shift the burden to colleagues created a powerful disincentive to attend to personal health needs or illness. Individuals who pointed out the inherent problems of this approach were often marginalized as being “uncommitted” or “weak."From the demographic perspective, physicians in this era were predominantly men whose spouses or partners did not have a career of their own. This arrangement allowed the spouses and partners of physicians to devote greater time to “keeping things running on the home front” even though the physician was often absent or devoted little time to these activities. The practice environment was less consolidated, with fewer physicians a part of large group practices. Electronic health record (EHR) use was not widespread, and measures of patient satisfaction and quality were not routinely assessed. In part because of the different structural characteristics of health care delivery at the time, physicians had greater autonomy, less oversight, and more control over the practice environment. Nonetheless, payers and regulators in this era used a “gotcha” approach to auditing payment and documentation that communicated a lack of trust and questioned the integrity of all physicians on the basis of the unprofessional behavior of a few.At the organizational level, there was limited if any attention to the impact of administrative decisions or regulations on physicians' work life. The concept that quality of care was a system characteristic had only begun to take hold. If medical errors occurred, the default was to blame the individual. This typically took the form of accusatory “root cause analyses” and morbidity and mortality conferences that subjected junior physicians to humiliation and shaming by supervisors and peers. The message conveyed was that the physician should be all-knowing and able to overcome every deficiency of the health care delivery system to ensure optimal care for patients under any circumstance (ie, physicians were supposed to have deity-like qualities).There was inattention to the impact of physicians' personal well-being on the quality of care they provided patients. Institutional needs were prioritized above patient and clinician needs, and there was no appreciation of the economic implications of physician distress on the financial health of the organization. During this time, the professional culture of medicine was characterized by a mindset of perfectionism that reinforced the concept of physician as deity. This framework discouraged vulnerability with colleagues, encouraged physicians to project that they had everything together (“never let them see you sweat”), and contributed to a sense of isolation. To the extent there was dialogue about physician distress, the focus was on individuals rather than the system or practice environment. Collectively, all these factors contributed to physicians’ professional identity subsuming their human identity. There were no limits on work, and the concept of boundaries between personal and professional life was considered a lack of commitment. To the extent there was attention to “physician wellness,” it centered on the concept of self-care: healthy diet, exercise, stress reduction, and getting enough sleep when not on duty. The Present: Physician Well-being 1.0Over time, increasing evidence and research began to change many of these historical paradigms. The “Physician Well-being 1.0” phase, to some extent, began between 2005 and 2010 and largely continues to present day. This phase has been characterized by knowledge and awareness. National studies began to chronicle the prevalence of distress among medical students, residents, and practicing physicians as well as trends in distress over time. Publication of these studies in peer-reviewed journals also began to result in headlines in the widely disseminated physician press (ie, “throw-away” journals; Medscape) with occasional pickup by the lay press. Importantly, the repercussions of physician burnout and other forms of occupational distress (eg, moral injury, fatigue/exhaustion) began to be recognized and to have an impact on conversations within the health care delivery system. The personal repercussions of physician distress (eg, broken relationships, problematic alcohol and substance use, depression and suicide) began to establish a moral and ethical case for action. Research also demonstrated the links between physician well-being and quality of care, including medical errors, patient satisfaction, and professional behavior. This evidence began to bring together a broad coalition of stakeholders concerned with clinician well-being and resulted in expansion of the triple aim of health care (improving patient experience, reducing the cost of care, advancing population health) to a quadruple aim that included clinician well-being. Other studies established links between physician burnout and clinical productivity as well as turnover, which drew attention to the economic costs of physician burnout for health care organizations and society. The demographic profile of physicians in this era evolved, with gender parity among medical school matriculates and an increasing proportion of women among the practicing physician workforce. More physicians were in 2-career relationships that assumed increased involvement of physicians in home responsibilities. The historical pattern of professional identity subsuming human identity shifted to a dual role and the need to “balance” personal and professional identities (ie, work-life balance). In parallel with these demographic changes, tremendous change occurred in the training and practice environment. Residency and fellowship training transitioned to a competency-based framework, and substantial, new limits on work hours were instituted. Consolidation of medical practices occurred, resulting in a majority of physicians working in employed practice models. Use of the EHR became widespread with the passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act in 2009, which defined and tied reimbursement to “meaningful use” of EHRs. Although organizations also began to appreciate the administrative impact of the EHR on physicians the response was to provide opportunities for physicians to learn “tips and tricks” to become more efficient in their ability to use suboptimal technologyIn an effort to quantify performance, organizations began to evaluate physicians using a host of new metrics, including measures of patient satisfaction, quality, cost, and productivity. Physicians became familiar with terms such as relative value unit generation, visit/billing targets, payer mix, service lines, top-box score, and net operating income. This contributed to a perception of misalignment between the professional values of physicians and the motives and priorities of their organizations. At the organizational level, awareness of the system nature of the problem began to develop. The response, however, typically remained focused on individual-level solutions and centered on providing treatment for physicians in distress (eg, mental health resources, peer support) as well as cultivating personal resilience through interventions such as mindfulness-based stress reduction. Despite these efforts, state licensure questions and stigma about mental health conditions remained a barrier to seeking help. Organizations began to view addressing physician distress as a necessary cost center, but, to the extent they allocated resources to advance physician wellness, they viewed it primarily through a “return on investment” mindset. As they considered addressing defects in the practice environment, organizations viewed the issue as a zero-sum game problem. This mindset suggested that the only way to relieve physicians from excessive workload and administrative burden was to shift this work to others. This framework suggested that system approaches to improve physician well-being would invariably worsen the well-being of other members of the health care team, resulting in inaction. At the professional level, discussions about a “culture of wellness” began to take hold but tended to focus on a message that encouraged physicians to “take care of themselves and become more resilient.” Physicians began to express frustration that this approach failed to address the underlying problems in the practice environment that were the core issue. Some physicians suggested that health care administrators were the root cause of the problem. That oversimplification was neither accurate nor constructive and led to divisiveness and reciprocal scapegoating (physicians blame administrators; administrators blame physicians) that drove a wedge between physicians and the individuals they needed to work with to improve the practice environment. Although physicians argued about what label best described their occupational distress and how to measure it, there was agreement that the problem was pervasive and that the practice environment was the issue. Acceptance that distress was widespread created openness for more physicians to discuss occupational challenges. This helped move physicians who were struggling in isolation to realize they were not alone and created greater willingness to discuss distress with colleagues. The Future: Physician Well-being 2.0Around 2017, vanguard institutions began to transition to the Well-being 2.0 phase. This transition has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which illustrated the foundational importance of clinician well-being to health care delivery systems and the profound impact that work characteristics have on well-being. The Well-being 2.0 phase is characterized by action and system-based interventions to address the root causes of occupational distress. The focus in this phase shifts away from individuals toward systems, processes, teams, and leaders. The importance of transitioning to the Well-being 2.0 phase was validated by the National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-being and the formal report from the Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-being released in late 2019. The scapegoating and finger-pointing that divided physicians and administrators in the Well-being 1.0 phase are replaced with a mindset of physician-administrator partnership to create practical and sustainable solutions. There is acceptance that physicians are subject to the same human limitations that affect all human beings, with attention to appropriate staffing, breaks, and rest as a part of performance. This phase builds from a foundation that burnout is codified as an occupational syndrome by the World Health Organization; harmonized definitions for burnout have been established; instruments to assess the syndrome have been developed, validated, and crosswalked; the neurobiology of occupational distress has been recognized; and the distinction between burnout and depression has been clarified. At the organizational level, the mindset in this phase centers on cultivating well-being and preventing occupational distress rather than simply reducing burnout. Senior leaders, such as Chief Wellness Officers, are appointed to address system-based drivers, and the infrastructure and resources to enable these leaders to drive organizational change are established. The principles of human factors engineering and design are embraced. The organizational focus shifts from patient needs to a people focus that attends to the needs of all individuals in the practice environment as both necessary and mutually beneficial to achieve the desired outcomes. This includes caring for the team and creating an organizational environment that attends to leadership, professionalism, teamwork, just culture, voice and input, and flexibility. The needs of individual clinicians, including sleep and work-life integration, are acknowledged and supported. In the Well-being 2.0 phase, the organization transitions from viewing wellness as a necessary cost center to viewing it as a core organizational strategy. The resource allocation mindset shifts from a return on investment framework to value on investment.From a demographic perspective, it is recognized that there is an equal mixture of men and women physicians and that most physicians are in 2-career relationships with shared duty for personal and family responsibilities. To enable people to meet these responsibilities, organizations create flexibility in the practice environment that allows physicians to meet both personal and professional obligations. This provides organizations a competitive advantage in recruitment and retention and allows physicians to work full-time and still accommodate personal needs rather than having to work part-time to do so. At the individual level, physicians have transitioned from a mindset of balancing personal and professional identities to one of integrating professional identity and personal identity into a single identity that encompasses human, personal, and professional dimensions. The intersection between diversity, equity, and inclusion to wellness is recognized. Although these are distinct domains, promoting antiracism and addressing threats and system factors that undermine diversity, equity, and inclusion are appreciated as foundational to efforts to advance clinician well-being. Consistent with this premise, more authentic conversations about organizational deficits in these domains occur in concert with action. At the professional level, the emphasis shifts from a culture of wellness to a culture of vulnerability and self-compassion, which acknowledges that physicians are not perfect, that they will make mistakes, and that they need to be vulnerable and support one another. Physicians recognize and acknowledge that they may have an Achilles’ heel as it pertains to perfectionism and self-criticism and dedicate themselves to developing skills to address these mindsets. Supporting colleagues involves creating not only connection but also community involving shared experience, mutual support, and caring for each other. Training programs embrace these principles and work to actively develop these qualities as core dimensions of competence as well as holistically cultivating residents’ and fellows’ well-being. Call to ActionWe have now internalized the lessons of the Well-being 1.0 phase, and vanguard institutions have begun to move to the Well-being 2.0 phase (Table). The profession, organizations, leaders, and individual physicians should act to accelerate this transition. TableCharacteristics of the Different Phases of the Physician Well-being Movement

EHR, electronic health record. At the broader professional level, physician leaders and professional societies must embrace the physician as human mindset rather than the physician as hero mindset. This mentality should permeate the values transmitted to the next generation of physicians at the earliest phase of training both cognitively and in the structure, design, and expectations of the clinical training process. This will require promulgating the core values of the profession (commitment to patient needs, service, altruism) along with the realities of human limitations and the concept that healthy boundaries, appropriate limits on work, work-life integration, and attention to personal needs are part of professionalism. These values should be embraced by the established members of the profession and care taken to responsibly impart them, along with other core values, to physicians in training. Deliberate efforts to change the professional culture of perfectionism to a culture of excellence in combination with self-compassion and growth mindset must be pursued. At the organizational level, the transition to Well-being 2.0 requires a shift from awareness to action. It requires organizations to establish the leadership, structure, and process necessary to foster sustained progress toward desired outcomes. This involves addressing system factors that drive occupational distress and reduce professional fulfillment. It includes attention to the efficiency of the practice environment and dimensions of organizational culture that can promote or inhibit well-being. Organizations must embrace human factors engineering and pursue system redesign that creates sustainable workloads, provides coverage when physicians are ill, and incorporates appropriate breaks and rest. Health care organizations must deepen their commitment to leadership development, increase receptivity to input from health care professionals, make a more authentic commitment to teamwork and optimization of team-based care, and foster an environment built on trust. For leaders, accelerating the transition to Well-being 2.0 requires attending to the leadership behaviors that cultivate professional fulfillment for individuals and teams. This includes caring about people always, cultivating individual and team relationships, and inspiring change. It requires both physicians and administrative leaders to foster a collaborative relationship and to engage in partnership to redesign and implement necessary changes. Working together to develop a shared sense of purpose and to create alignment of organizational and professional values is a foundational step. At the individual level, the transition to Well-being 2.0 requires mindfully considering how to incorporate self-compassion, boundaries, and self-care alongside other professional values. Physicians must acknowledge that they are subject to normal human limitations and attend to rest, breaks, sleep, personal relationships, and individual needs. They must reject the role of victim, stop blaming administrators, and be part of the solution. This requires casting off the narrative that physicians are powerless to effect change in large health care organizations (learned helplessness), which is not true and is a barrier to creating the system change that is needed. Catalyzing such change requires physicians to work in partnership with operational leaders to improve the practice environment and health care delivery system. Physicians must hold fast to the belief that it is a privilege to be a physician and that honor requires dedication to others and responsibilities that involve sacrifice. That duty to patients and society, however, has limits. Times of intense work must be offset with appropriate time to recharge. Individual physicians are responsible to learn to simultaneously navigate the challenges of their career and attend to personal needs. This includes cultivating self-compassion and attention to self-care (sleep, exercise, rest) and work-life integration. Individual physicians must also preserve a strong commitment to supporting their colleagues. They should strive to create community with one another, including relationships that enable vulnerability and mutual support. Roadmaps to facilitate these changes at the profession, organization, leader, and individual level have been developed, studied, and published. Organizations and individuals that have not started their journey should use these roadmaps as a place to begin. All physicians should work to accelerate progress in their sphere of influence. Continued research and organizational discovery will enhance current knowledge and provide new learnings to help the Well-being 2.0 phase flourish. As this phase matures, the contours of a yet to be defined Well-being 3.0 phase will inevitably develop. ConclusionThe last 3 decades have a been a time of tremendous progress for the field of physician well-being. We have moved from the era of distress, characterized by ignorance and neglect, to an era of awareness and insight. Leading institutions have now transitioned from knowledge to authentic action. Robust research and application by leading institutions has been the key to the maturation of the field. The profession, organizations, leaders, and individual physicians should commit themselves to accelerating this transition to the Well-being 2.0 era. Now is the time for action. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(21)00480-8/fulltext

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jan 11, 2023 |

A Curriculum to Increase Empathy and Reduce Burnout |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Mariah A. Quinn, MD, MPH; Lisa M. Grant, DO; Emmanuel Sampene, PhD; Amy B. Zelenski, PhD ABSTRACT Purpose: Empathy is essential for good patient care. It underpins effective communication and high-quality, relationship-centered care. Empathy skills have been shown to decline with medical training, concordant with increasing physician distress and burnout. Methods: We piloted a 6-month curriculum for interns (N = 27) during the 2015-2016 academic year at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The course included: (1) review of literature on physician well-being and clinical empathy, (2) instruction on the neurobiology of empathy and compassion, (3) explanation of stress physiology and techniques for mitigating its effects, (4) humanities-informed techniques, and (5) introductions to growth mindset and mindful awareness. To measure effectiveness, we compared empathy and burnout scores before and after the course. Results: The course was well-attended. Intern levels of burnout and empathy remained stable over the study period. In multivariable modeling, we found that for each session an intern attended, their emotional exhaustion declined by 3.65 points (P = 0.007), personal accomplishment increased by 2.69 points (P = 0.001), and empathic concern improved by 0.82 points (P = 0.066). The course was well-liked. Learners reported applying course content inside and outside of work and expressed variable preferences for content and teaching methods. Conclusion: Skills in empathic and self care can be taught together to reduce the decline of empathy and well-being that has been seen during internship. In this single-center pilot, resident physicians reported using these skills both inside and outside of work. Our curriculum has the potential to be adopted by other residency programs. INTRODUCTION Strong patient-physician relationships are essential for effective communication and support high-quality care. Clinical empathy is a critical skill in the cultivation of effective therapeutic relationships with patients. Empathy includes cognitive and emotional components, as well as intentions and behaviors that seek to alleviate suffering (ie, compassion and compassionate behaviors). There is no consensus definition of clinical empathy, but researchers have studied the impact of physician empathy primarily by assessing communication or relationship variables. These studies demonstrate positive outcomes for both physicians and their patients. For physicians, these outcomes include improved diagnostic accuracy, efficiency, self-efficacy and confidence, job satisfaction, burnout, rate of malpractice claims, and the cost of care.1–5 Patient outcomes include improved recall, comprehension, loyalty, trust, satisfaction with care, selfefficacy, treatment adherence in chronic disease management, health status, quality of life, safety, symptom management and function.6–12 In fact, a meta-analysis published in 2014 focused on randomized controlled trials in which the patient-physician relationship was the experimental variable, found a meaningful impact on health care outcomes across multiple disease states.12 There is a nuanced relationship between empathy and burnout. High personal distress and identification with a suffering patient can engender stressful or overwhelming suffering within the empathizer, raising the risk for burnout.13,14 However, research with trauma therapists demonstrates that well-developed empathy helps both patients and clinicians. This work suggests that “exquisite empathy,” described as “highly present, sensitively attuned, well-boundaried, heartfelt empathic engagement” is, in fact, sustaining and protective against burnout and compassion fatigue.15,16 Further, a study examining an intervention aimed at reducing personal distress via cognitive reappraisal compared with an intervention to augment compassion found that while both interventions improved subjects’ altruistic behaviors, it was the compassion intervention that was more protective against personal distress.17 These studies support the growing consensus that well-developed empathy protects physicians against burnout.18 Since progress through medical training consistently has been shown to correlate with reductions in empathy and epidemic levels of distress and burnout, interventions to support empathy skills and personal well-being are a critical necessity in residency programs.19,20. METHODS We developed a 9-session curriculum for internal medicine interns to strengthen empathy skills and reduce burnout. We hypothesized that a multimodal, neuroscience and humanities-informed curriculum would improve measures of empathy and burnout in this population and measured the course’s impact by examining burnout and empathy before and after course participation. Curriculum Development We performed a literature review to identify pedagogical techniques with relevance to the development of (1) skills in self-care to reduce burnout and emotional distress and (2) skills in effectively caring for others focused on empathic or compassionate care. We reviewed the medical and other health professions literature as well as the education, psychology, and neuroscience literature. Given evidence from prior programs that a one-size-fits-all approach will leave learner subgroups untouched, we decided to employ a multimodal approach.21 Components ultimately included in the curriculum are shown in Table 1. We also taught the concept of growth mindset at the beginning of the course to increase learner acceptance and uptake of content and bolster their confidence in learning these skills. Growth mindset is a belief that with effort, one can improve in a certain domain (eg, empathy).22 Course Logistics The course included 9 sessions ranging in length from 2 to 4 hours held on Friday afternoons spread over 6 months. We worked with residency program leadership (including program staff, chief residents, and the program director) to determine where in the weekly and daily schedule our curricular sessions would face the least competition and clinical coverage difficulties that could lead to resentment or low attendance. In this pilot year, the intern class was divided into 2 groups so only half of the interns would be gone from rotations at any given time. We randomized men and women separately into the groups to preserve gender balance. The schedule was provided to the interns at the beginning of the year, and we sent email reminders to all clinical teams at the beginning of each rotation with the schedule of sessions. We also sent reminder pages to the interns 1 to 2 hours before sessions. This project was reviewed and exempted by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board as Program Evaluation. Course and Program Evaluation All interns (N=28; 22 men, 6 women) were required to participate in the curriculum, but they could elect whether or not to participate in the curriculum evaluation, which all but 1 intern elected to do (N= 27). We gathered data during their orientation period, after 6 months of internship, and in the last month of internship. To protect interns’ privacy, the course creators did not have access to personally identifying information on any of the measures collected; their data were tracked using a nonidentifying study ID. Outcome measures included empathy, using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), and burnout, using Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Predictors included Mindset Assessment Profile (MAP)23–25 and an emotional styles inventory (ESI) that was collected during orientation and at the end of internship to understand the relationship among baseline emotional style, burnout, and empathy.26 The emotional styles inventory measures resilience, outlook, self-awareness, social intuition, sensitivity to context, and attention. Domains included in the outcome measures are summarized in the Box. If our curriculum were effective, we would expect to see stabilization or reductions in the MBI domains of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion and a stabilization or increase in personal accomplishment, as well as the IRI domains of empathic concern and perspectivetaking. We tracked attendance at each session. At the end of the course, we also evaluated favored course methods, skills used both inside and outside of work, and ongoing support for the course using free text entry. Statistical Analysis All pre- and post-data were analyzed using paired t tests for dependent samples. In order to understand how the course affected burnout and empathy, we performed multivariable modeling including the following predictors: mindset, emotional styles domains, cohort (to capture time of year), and session attendance. Given the correlations between predictors and instruments, collinearity was assessed among the predictor variables and was acceptably low to include all covariates in the model. Although we performed several comparisons between our burnout and empathy outcome variables and our predictors of interest, we did not adjust for multiplicity due to the exploratory nature of those analyses. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 and findings were statistically significant at P<0.05 (95% CI) RESULTS Of 28 interns, all participated in the course and 27 (96.4%) elected to participate in the course evaluation. The reason for the one intern’s nonparticipation was unknown. At baseline, the 2 cohorts did not differ significantly with respect to growth mindset, empathy levels, burnout, or emotional style, and burnout was present in 41% of interns (scoring high in emotional exhaustion or depersonalization, or both) with average scores in the moderate range for both. Detailed pre- to post-outcome measures, as well as the impact of session attendance on outcome measures, are shown in Table 2. Intervention Feasibility and Acceptability nterns attended a median of 7 of 9 sessions in both cohorts. However, there were more interns who attended fewer than 6 sessions in cohort 2 (attendance range 5-8 in cohort 1 and 3-8 in cohort 2). Most interns (74.0%) felt they had the support of other residents and faculty to attend the class. The other 26% reported feeling moderately supported and, of these, most reported that it was difficult to leave on call days or otherwise particularly busy clinical days. At course completion, interns were asked to rate their anticipated level of support for new interns attending the course the following year. The majority (92.5%) reported a high, unconditional level of support for the course in the future. By contrast, 2 respondents reported contingent support. For example, one intern said they would “do (their) best to get (their interns) to the course though patient care will continue to take precedence.” Use of Concepts and Favored Methods Interns reported utilizing concepts both in and outside of work. Skills learned in the improvisational theatre sessions, meditation or mindfulness practices, and specific empathic communication techniques were mentioned the most. Approximately 33% of interns specifically commented that naming emotions and the other skills taught as part of the empathic communication mneumonic NURSE (Naming, Understanding, Respecting, Supporting, Exploring) 27 were very helpful, both in their per sonal and professional lives. One stated that it was “extremely helpful in ‘defusing’ angry/frustrated patients.” Many interns made comments that meditation and reflection were very helpful, especially with managing their personal emotions: “When I am about to see a presumably ‘difficult’ patient in clinic, I definitely pause outside the room, take a deep breath, and then knock.” A few interns (14.8%) noted that they started using meditation and mindfulness more regularly. The fixed versus growth mindset was a new concept to many interns and, at the end of the year, 29.6% noted it as a concept that they either recalled or used during the year. One intern in particular recalled the growth mindset stating, “It took me a really long time to realize that I wasn’t alone in feeling kind of overwhelmed and underqualified. I think once I felt okay about not being 100% perfect at my job (and focus on growing, helping patients) I really got a ton better at my job!” Favored methods in the course also varied, but visiting the art museum and the improvisational theatre sessions were the most enjoyed. Many interns said they appreciated the opportunity to get away from the hospital to visit the art museum. The percentages of interns that reported each method as most enjoyable are listed in the Figure; many interns rated equal enjoyment of more than one method. Empathy and Burnout The pre- and post-course scores in all burnout and empathy subscales are shown in Table 2. The only measure that changed significantly was depersonalization, which appeared to increase. This could imply a decrease in empathy. However, in the model that included course attendance, there was no signficiant relationship between course attendance and depersonalization (P for beta=0.40). Course attendance significantly predicted reduced emotional exhaustion (P=0.007) and improved personal accomplishment (P=0.001). These findings suggest that without the course, burnout would have worsened over the course of the year, as expected historically. We compared our pilot interns’ empathy levels during the fall of their second year of residency to a group of historical second-year residents in our program who had not participated in the course, but were otherwise comparable due to their training level. The 27 residents who had taken our course vs the 34 historical residents showed improved IRI subscale scores in personal distress: 9.26 vs 11.67 (P= .03). All other domains did not reach significance, including perspective-taking: 21.26 vs 19.74 (P=0.18); empathic concern: 21.33 vs 19.94 (P=0.12); (fantasy, 18.15 vs 16.41 (P= 0.23). Improved empathy is shown on the IRI by increases in perspective-taking and empathic concern accompanied by decreases in personal distress. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS We developed a feasible and well-liked intervention to improve skills in the care of others and self, as measured by improvements in empathy and burnout concordant with course attendance. We found that including multiple modalities supported content delivery. While depersonalization scores, on average, worsened over the course of the year, we found that attendance in our course did not appear to predict this change and was associated with improvements in emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment, as well as a trend toward improvement in empathic concern. In addition, the course’s effect on empathy was sustained after the course ended—as assessed 3 to 9 months after course completion—in comparison to a historical comparison group. We found that different learners preferred different learning methods. This finding is consistent with the “CHANGES” study,21 which showed that learner characteristics interact with curricular content in ways that are critical for educators to consider. A “one-size-fits-all” curriculum with a single modality is unlikely to be as effective for all learners as a curriculum that includes different “hooks” and methods. We challenged ourselves to integrate a variety of methods and content into our curriculum, in order to increase the likelihood that any curricular arrow would find a target and stick, allowing us to engage all learners. The methods and concepts interns reported as useful, in both work life and outside of work, clustered around emotional intelligence, empathic communication, and mindfulness in the face of stress or adversity. We initially were surprised to find worsening depersonalization pre- to post-course, with no apparent effect of course attendance in multivariable modeling, as well as the apparently stable emotional exhaustion pre- to post-course, with an apparently protective effect from course attendance. We did not observe the historically expected increase in burnout over the course of internship in this group of interns.20 To better understand whether this was simply related to the overall educational environment at our institution, we were able to compare changes in burnout from orientation to mid-academic year for the intern class entering the year after our pilot year to institutional comparisons (other nonprocedural training programs including pediatrics, emergency medicine, psychiatry, pathology, neurology, radiology, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology). In this group, we saw that between orientation and mid-year, the internal medicine interns—all of whom received our course—had depersonalization change by -0.11 and emotional exhaustion change by -0.91 (P= 0.92 and P=0.7, respectively), while in the other nonprocedural interns depersonalization changed by 1.6 and emotional exhaustion changed by 6.68 (P=0.22 and P=0.005, respectively). Strengths of this study include excellent course participation, which heightens our confidence of the course’s feasibility and acceptability. We also used common and validated outcome measures. Study limitations include the limited power that comes from a small sample size and multiple comparisons made as part of the analysis of this evaluation. The fact that the intervention occurred at a single center by a single teaching team may limit the generalizability of our findings. Finally, we chose for inclusion as predictor variables the subscales of the Emotional Styles Inventory, as published by Richard Davidson, PhD.26 This was selected because we have found it helpful when coaching residents on doctor-patient relationship issues to identify contributors and potential solutions. While it is not a validated instrument, it contains domains we have found pertinent as educators, and our analysis confirms that it maps to important outcomes. An additional limitation is the potential for reverse causation. For example, perhaps less emotionally exhausted interns were more likely to be able to leave their services to come to the sessions. Limitations above notwithstanding, our findings suggest that skills in self and others are not mutually exclusive and that, for physicians, these domains can be linked and fruitfully taught together. Future directions include further development of this course to achieve graduated levels of difficulty so that trainees can retrieve and utilize the concepts learned during the most difficult clinical encounters and practice scenarios, in addition to determining whether other learner groups would benefit similarly from this curriculum to assess reproducibility and generalizability https://wmjonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/119/4/Quinn.pdf

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jan 11, 2023 |

5 Ways To Develop Your Emotional Intelligence |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Emotional intelligence (EQ or EI) is one of the strongest indicators of success in business. Why? EQ is not only the ability to identify and manage your own emotions, but it’s also the ability to recognize the emotions of others. This study by Johnson & Johnson showed that the highest performers in the workforce were also those that displayed a higher emotional intelligence. And according to Talent Smart, 90% of high performers in the work place possess high EQ, while 80% of low performers have low EQ. Simply put, your emotional intelligence matters. Many of my clients often come to me frustrated with their managers, ready to quit because of the poor relationship they have with their boss. When I listen to what’s going on, it’s usually that these leaders aren’t demonstrating high levels of emotional intelligence. Don’t let that be you! Here are five ways to develop your emotional intelligence. 1. Manage your negative emotions. When you’re able to manage and reduce your negative emotions, you’re less likely to get overwhelmed. Easier said than done, right? Try this: If someone is upsetting you, don’t jump to conclusions. Instead, allow yourself to look at the situation in a variety of ways. Try to look at things objectively so you don’t get riled up as easily. Practice mindfulness at work, and notice how your perspective changes. 2. Be mindful of your vocabulary. Focus on becoming a stronger communicator in the workplace.Emotionally intelligent people tend to use more specific words that can help communicate deficiencies, and then theyimmediately work to address them. Had a bad meeting with your boss? What made it so bad, and what can you do to fix it next time? When you can pinpoint what’s going on, you have a higher likelihood of addressing the problem, instead of just stewing on it. 3. Practice empathy. Centering on verbal and non-verbal cues can give you invaluable insight into the feelings of your colleagues or clients. Practice focusing on others and walking in their shoes, even if just for a moment. Empathetic statements do not excuse unacceptable behavior, but they help remind you that everyone has their own issues. 4. Know your stressors. Take stock of what stresses you out, and be proactive to have less of it in your life. If you know that checking your work email before bed will send you into a tailspin, leave it for the morning. Better yet, leave it for when you arrive to the office. 5. Bounce back from adversity. Everyone encounters challenges. It’s how you react to these challenges that either sets you up for success or puts you on the track to full on meltdown mode. You already know that positive thinking will take you far. To help you bounce back from adversity, practice optimism instead of complaining. What can you learn from this situation? Ask constructive questions to see what you can take away from the challenge at hand. Emotional intelligence can evolve over time, as long as you have the desire to increase it. Every person, challenge, or situation faced is a prime learning opportunity to test your EQ. It takes practice, but you can start reaping the benefits immediately. Having a high level of emotional intelligence will serve you well in your relationships in the workplace and in all areas of your life. Who wouldn’t want that? https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashleystahl/2018/05/29/5-ways-to-develop-your-emotional-intelligence/?sh=5cc64fe6976e |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 23, 2022 |

Patients' Bad Behavior Provokes Burnout in Physicians: Study |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|